Some of the most recent impactful medical advances have happened in studying the gut-brain axis.

Imagine standing at the edge of a cliff, looking into a pool of water. You’ve summoned the courage to jump. Chances are, just *thinking* about it gives you butterflies in your stomach. You can thank the gut-brain axis for those butterflies.

What is the gut-brain axis?

We can think of the gut-brain axis as the conversation that occurs between our two brains: the central nervous system and the enteric nervous system.

The central nervous system gets more play. But the enteric nervous system is the unsung hero.

The enteric nervous system controls the release of some neurotransmitters including gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and serotonin. These neurotransmitters travel from the gut to the brain via the vagus nerve (the body’s longest nerve, emerging directly from the brain).

Chemical signals travel in both directions. That is why people with gut issues are more likely to have mood imbalances, anxiety, depression, etc. It’s also why someone with a history of a traumatic brain injury is likely to have gut dysbiosis. And someone with a leaky gut is likely to have cognitive symptoms.

Our happy hormones are made in the gut.

Many of us instinctively believe that our mood is determined by what’s happening in our heads. Certainly our thoughts, beliefs, and the stories we tell ourselves all influence our experience of emotions.

But there’s mounting evidence that shows that there are key physiological components to our mood.

Nutrient co-factors are essential to help our body create healthy neurotransmitters. For example, zinc insufficiency or copper overload can contribute to anxiety. Vitamin B6 deficiency can inhibit a person’s ability to make serotonin or dopamine. Methyl b and folate imbalances are associated with mood disorders.

The microbiome itself produces most of the neurotransmitters that help us feel happy. If our gut isn’t functioning optimally, we are much more likely to feel depressed.

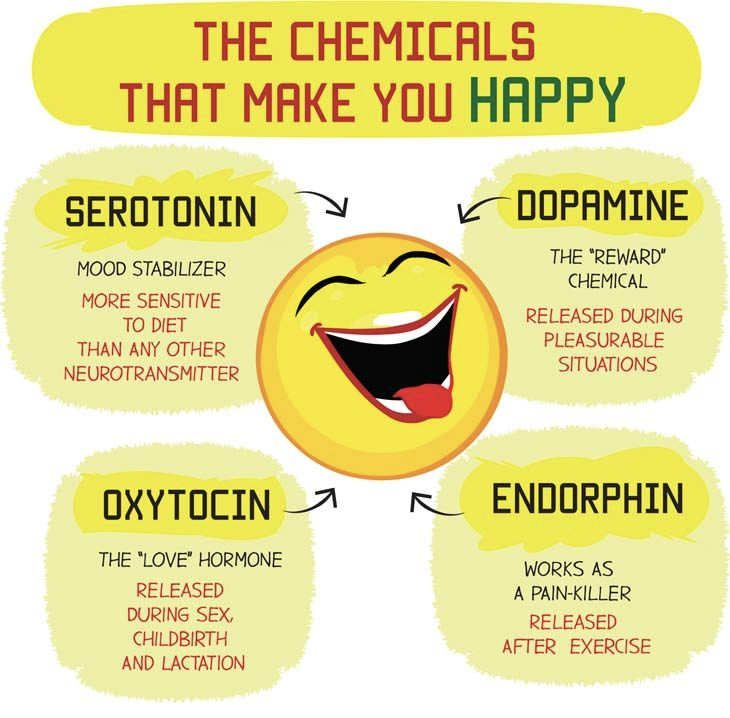

Dopamine, oxytocin, endorphins, and serotonin are the four happy hormones, and they’re all produced, at least in part, by the gut.

Endorphins are natural pain relievers and are released with exercise.

Dopamine is the hit you get when you complete your Wordle in 2 tries.

Serotonin is your mood regulator, amongst other things.

Oxytocin is the love and orgasm hormone. But it also regulates GI motility. A recent study shows that low serum oxytocin level correlates with gut dysbiosis. Some microbes naturally increase oxytocin within the brain.

Boosting oxytocin through probiotics may improve sociability, impulse control, and behaviors such as empathy and altruism.

For example, in one study, mice given the bacterium l reuteri (which produces oxytocin) took better care of their young. Oxytocin is also expressed in nerve cells throughout the GI tract.

It’s a two-way street

Inflammation travels in both directions.

The microglial cells, or the brain’s immune cells, will be activated if the gut is inflamed.

The communication between the gut in and the brain works in both directions. Stress, among other things, causes inflammation. Negative thoughts send signals from the brain to the gut that will impact the production of our happy hormones. Ramp up the production of stress hormones and downregulate the production of happy hormones. Once again, it’s a positive feedback loop.

We’re starting to realize that mindfulness exercises improve our microbiome and the production of neurotransmitters. Rumination and negative thoughts have physiological impacts on the body.

This is why meditation, self-compassion, and spending time with people you love positively impact gut health and immunity.

Serotonin is made in the gut?!

95 % of serotonin or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) is produced in the gut. Therefore, any chronic gut issues such as SIBO, dysbiosis, leaky gut, IBS, etc., will result in impaired serotonin production. Serotonin is also important for proper digestion and absorption, thus forming a vicious cycle.

Serotonin regulates your mood. Balanced serotonin levels help us feel calmer, happier, more focused, and less stressed. When we are chronically stressed, our stress hormone, cortisol, rises, which impairs serotonin’s ability to function properly.

This leads to depression.

Serotonin supports digestion. Low serotonin levels can lead to constipation, and elevated levels can lead to diarrhea. Serotonin supports optimal sleep. Serotonin helps with blood clotting. Serotonin promotes bone health.

Serotonin is so important to our health that many people are on prescription drugs that increase circulating serotonin levels. Drugs like Paxil and Prozac are SSRIs or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. As it sounds, they keep more serotonin in circulation by blocking the reuptake of it.

The problem is too much serotonin can also be problematic, and there are many undesired side effects. For this reason, when possible, I like to help my patients increase their serotonin levels.

What can I do to boost my serotonin levels?

Tryptophan is a precursor to serotonin. Tryptophan also supports the natural production of melatonin, which helps us to sleep well and wake up refreshed (and ready to produce serotonin). If our serotonin is inadequate, sometimes it starts with too little tryptophan intake and production.

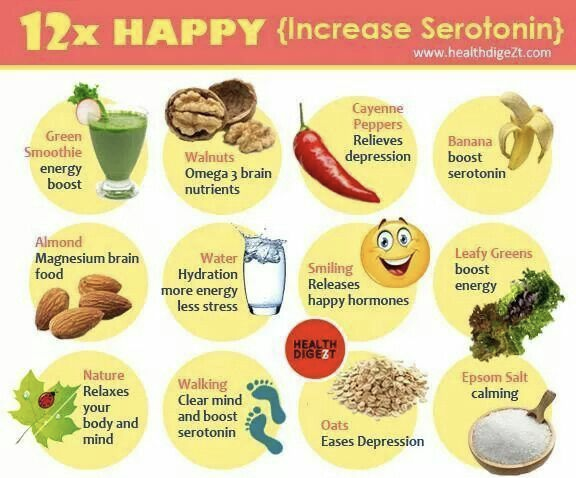

Eat

One easy way is to eat more tryptophan-rich foods, including chicken, turkey, fish, fruits such as bananas, apples, and prunes.

Exercise

Exercise increases your body’s ability to produce serotonin indirectly. Aerobic exercise increases tryptophan levels in your bloodstream.

Get outside

Time in the sun increases serotonin levels.

Hydrate

Staying well-hydrated is also important to optimal serotonin production.

The photo to the left is a great visual reminder of ways to increase your serotonin.

Do probiotics help with mood?

Alterations in the microbiome have been shown to profoundly influence the neurotransmission of serotonin in the peripheral and central nervous systems.

Probiotics in the GI tract improve symptoms associated with depression by increasing the production of free tryptophan and increasing serotonin availability. The increase in serotonin facilitates the regulation of the HPA axis and reduces depressive symptoms.

Several gut bacteria are missing in people with depression. Imbalances in gut flora can lead to serotonin imbalances. Many lactobacillus and bifidobacterium strains have been studied with respect to mental health and seem to show the most beneficial effects.

When we consume L reutri, it’s shown to increase oxytocin levels and decrease cortisol levels.

Sleep and probiotics: Impaired sleep is a common symptom of major depressive disorder, most commonly manifested as difficulty in falling asleep, staying asleep, unrefreshing sleep, and daytime sleepiness. Serotonin is a neuromodulator of sleep. As probiotics have been shown to affect serotonin levels via the gut-brain axis, probiotics also likely affect sleep.

A systemic review in 2017 showed improvements in effects on mood, effects on stress and anxiety, and effects on cognition with probiotic supplementation. Probiotics had the most significant effect on symptoms of anxiety.

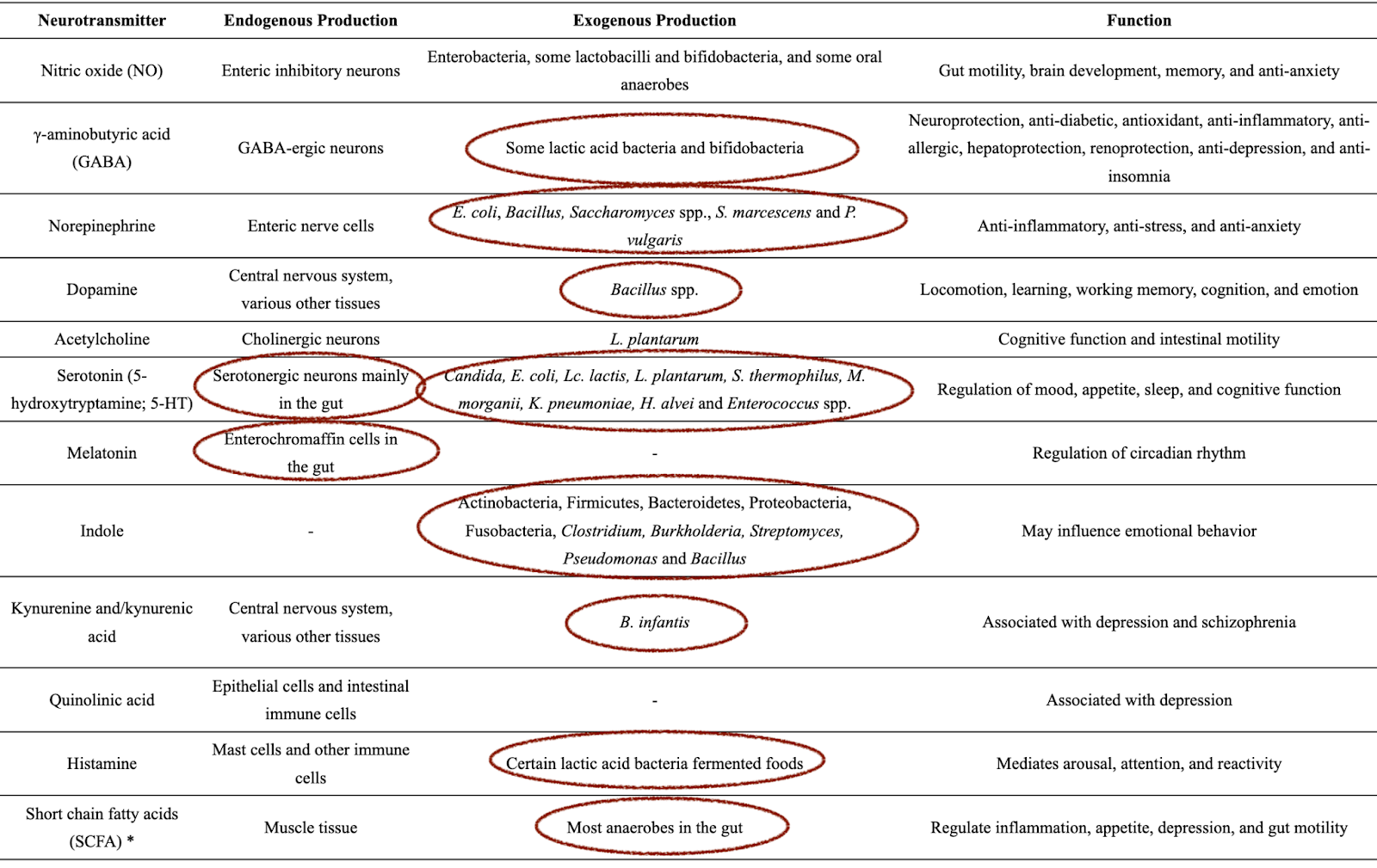

The table below indicates where our primary neurotransmitters are produced in our body. Notice that for most neurotransmitters, the production is a combination of endogenous (meaning produced by our body) and exogenous (meaning produced by our microbiome). If we don’t have adequate strains of the various species needed to produce serotonin, our serotonin levels will likely not be balanced. Further studies are needed, and supplementation with the targeted strains of probiotics will likely prove helpful in optimizing our neurotransmitter production. We recommend various strains and brands of probiotics to our patients depending on what their symptoms are and what hormones are out of balance.

How do probiotics help with mood?

The bottom line is they help with inflammation which helps our endogenous production of feel-good hormones. They also help produce feel-good neurotransmitters directly.

Increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), and C-reactive protein (CRP) are repeatedly observed in people experiencing depression.

Increased inflammation activates the HPA axis and alters neurotransmitter metabolism.

The inflammation is caused by increased intestinal permeability or “leaky gut.” This allows toxins and other forms of waste to leak into the bloodstream.

These endotoxins cause the body to mount a global immune response. It is hypothesized that probiotics may exert their effects on the central nervous system by improving the integrity of the gastrointestinal lining, reducing the ability of the endotoxins to leak into the bloodstream, and, in turn, decreasing global inflammation. Reducing inflammation improves the regulation of the HPA axis and neurotransmitter activity.